Red Wolf Editions Spring 2021

Theme: The Reaper

It may be that when we no longer know what to do

We have come to our real work,

And that when we no longer know which way to go

We have come to our real journey.

The mind that is not baffled is not employed.

The impeded stream is the one that sings.

–Wendell Berry

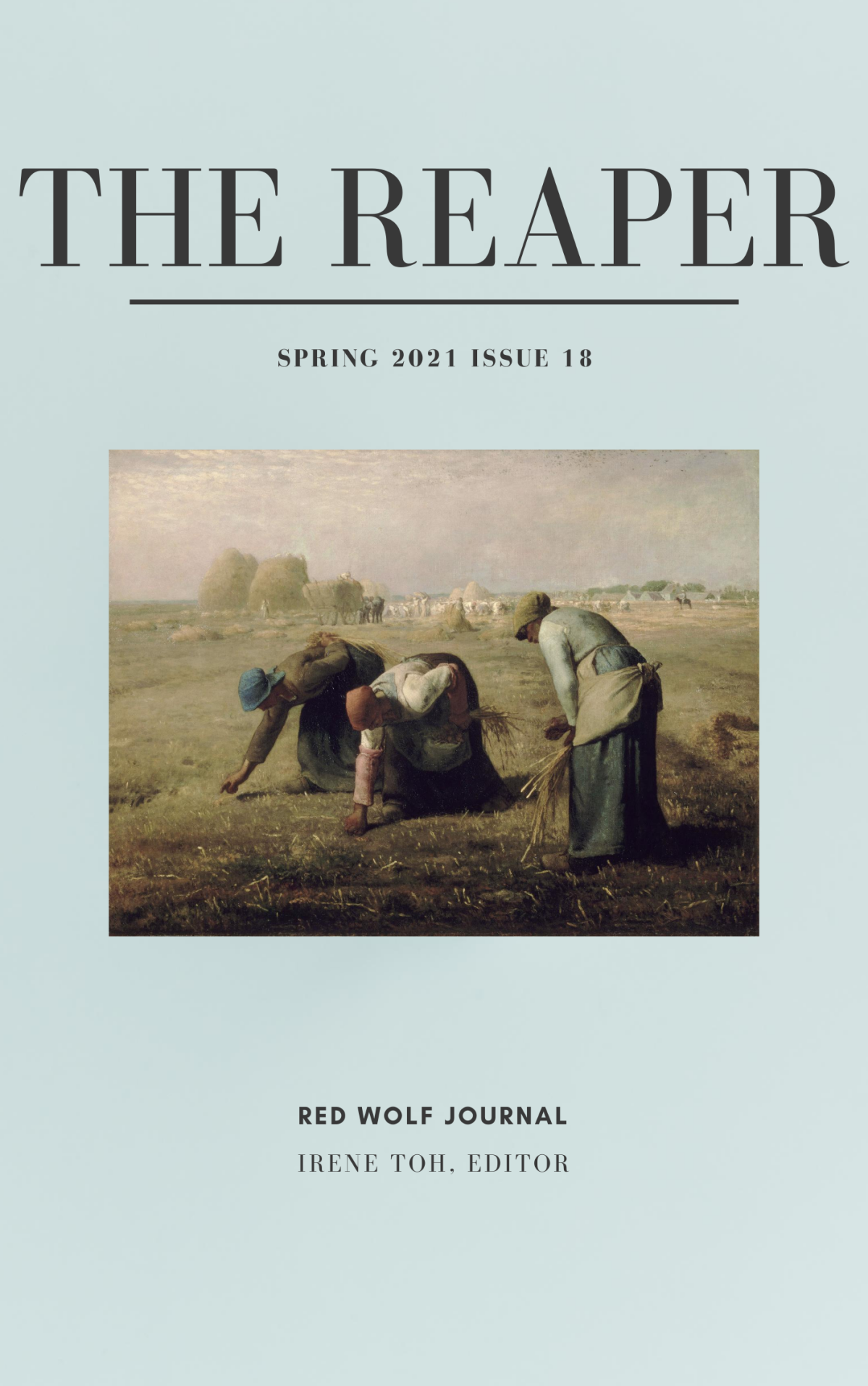

For a time during the coronavirus spread, was death not so far from your mind? It was constantly on mine, as death tolls climbed in Italy, then Spain, then the UK, and the US, the fact that death was real, your own death you know, should you be stricken too. So the title of the Spring 2021 issue should come as little surprise, I suppose, to your mind, to refer to the Grim Reaper. But the reaper I really have in mind, is the one in the fields, reaping what was sown. Jean-François Millet’s painting depicts a rich harvest in the background, which can be seen as, in a particular context, your life’s work. We have all labored, in our lives, to bring about value and sustenance, to oneself, to our families, to the world at large.

In Greek mythology, Cronos was conflated with Father Time, wielding the harvesting scythe. According to one creation myth, a cut was made between heaven and earth thus enabling the beginning of time and of human history. The “castration” of heaven, as this event was referred to, was by means of a sickle. So it is that the god of time is associated with “calendars, seasons, harvests” (Wikipedia). In time, if we labor, comes harvest season. It is the culmination of human effort, your effort no less, and metaphorically speaking, what you do with your time shapes everything that comes after. Life is about the effort you put in. In the end, it shapes your identity and carves out your name, immortalizes it. Ah well, maybe I’m romanticizing, about the immortality bit. The results are often temporal.

There’s nothing romantic about labor. The gleaners, in Jean-François Millet’s time, were the peasants who perform a back-breaking job to collect what’s left over at the end of harvest. One woman searches for stray grains on the ground, one collects the grains and the third ties them all together. They’re collecting the crumbs, which could function as metaphor for how society, then and now, works. Then, as now, the landowners enjoyed the better part of the harvest, while the peasants who undertook the hard labor collected the meagre crumbs. In this bucolic picture, the painter valorized the rural working class by making the peasant women his subject. It made a commentary about the social divide by situating the harvest of wheat in the far distance. The contrast between lack and plenty—does that move you to write a poem?

What moves you to write a poem? Poems may be viewed as small culminations of a poet’s life experiences. A seasonal harvest. They take what comes at hand, catalog particulars from real and imagined life, and somehow become radiant with meaning. In creating our poems, we’re leaving echoes of ourselves in a real or imagined way. Poems come into the awareness of another, a reader, and we become part of this eddying world of meaning that we’ve created for ourselves, a verge of knowing. Written in a fit of spiritual urgency, poems are of experience born and so may help us find our sense of bearing in the temporal world.

I’m after your harvest. The afterglow of your experience. Perhaps you want to reflect on the idea of labor, the work that mothers do, or grandparents, or doctors, or whoever had impressed you in some way. Perhaps you want to reflect on some inequalities that you’d witnessed. You’d definitely want to write about your writing life, since you’re a poet in practice. Actually, just write about anything that you know, the person you’d known and loved, and perhaps lost, the past opportunities, anything you’ve reaped in your imagination. It behooves me to say now is the time to reap the language of poetry, which in my favorite definition is to get to the “furnace of meaning in the human story” as Mary Oliver said.

Perhaps you are at a stage of life, when that old adage, reap what you sow, comes to play. I told my sons the other day that I’m now resting on my laurels. I labor no more, I’m at rest, at ease. Perhaps my work has come to a completion, and like the gleaners in Jean-François Millet’s painting, I’m just picking the leftovers, what remains for me to finish up. When you come to the end of labor, it’s harvest season. It’s an outpouring, a bounty. Then of course you wait. Will the next season come? Or will the Grim Reaper?

Which is the iconic harvest poem? To me it’s this one.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

—John Keats, “Ode to Autumn”

So what was the flowering you had, what fruit have you gathered? Is it then a looking back? What intimacies? Were they bittersweet? What were those events that had watered your soul? What is your summation? For isn’t it true that whatever happened happened for a reason, for something that is within you, your soul, what you came here for? I leave you with these lines from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”.

And as to you Corpse I think you are good manure, but that does not offend me,

I smell the white roses sweet-scented and growing,

I reach to the leafy lips, I reach to the polish’d breasts of melons.

Finally you might want to think about the work that poems do, by naming all the things you’ve named with words, but to harvest meaning beyond the words, all for your readers to glean. And are you indeed the reaper?

Read our submission guidelines here. Please check back on our site to see if your poem has been selected. We will not be sending out any acceptance or rejection letters.

Submissions period: September 2020 to February 2021. Selected poems will be posted on this site as well as this site and compiled into a PDF release in Spring 2021.

Good writing.

Irene Toh

Editor

Spring 2021 Edition